Picasso & His Muses: The Women That Made His Career

Picasso is one of the most prolific painters of the 20th century, a pioneer in the Avant-Garde movement, and whose artistic genius is considered unparalleled. However, Picasso also stands as a figure of male chauvinism.

Scholars and art historians know that Picasso was a profoundly personal artist, taking inspiration from his life to reflect directly into his artwork. Not excluded are Picasso’s muses and lovers. However, the reality of these relationships and the role of Picasso is often disregarded and separated from his own artwork.

Breaking The Myth of Pablo Picasso

From age 10, Picasso was exposed to the exploitation of women by his father. They would frequent brothels in Spain, where a young Picasso was introduced to sexuality at a tender age, and his misogynistic tendencies were nursed.

Picasso’s first period was his two-and-a-half-year “blue period” from 1901 to 1904, which he spent between Barcelona and Paris. Picasso looked for his subject material in the brothels of Paris and frequently visited women’s prisons that provided him with free models. All of the characters in these works are lonely and sad, almost desperately so.

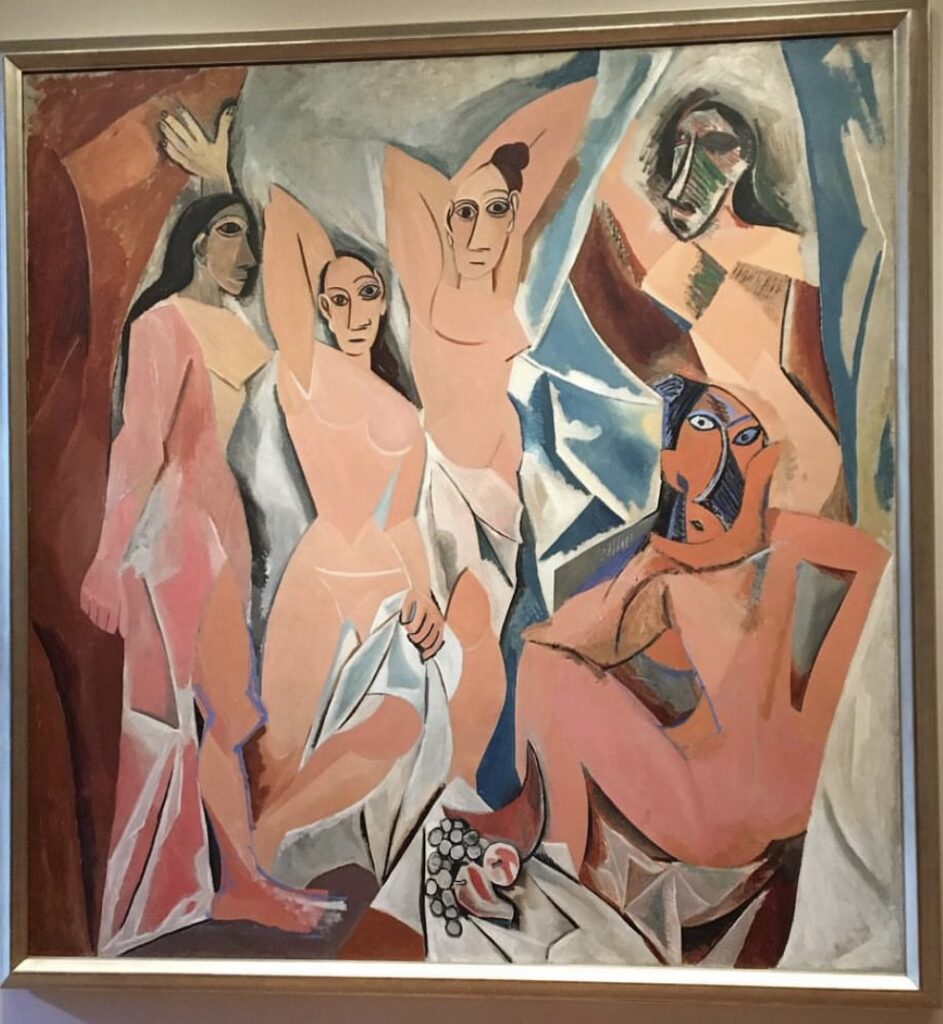

The prostitutes Picasso interacted with would later inspire arguably his most famous work, Les Demoiselles D’avignon (1907). The painting, which can be found in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, depicts a group of prostitutes in his signature cubist motif. The harsh lines and sharp angles illicit a derogatory and unpleasant stance about these women.

His overt sexuality can be seen through his most obsessive motif, the female nude. Through his long career and ever-changing styles and moods, the depiction of women remained consistent.

Sporadic changes are often attributed to the presence of a new love interest or the waning of an old one, or both. Picasso’s infamous remark that women are “goddesses or doormats” has rendered him detestable to feminists, yet his lovers were never in short supply.

Throughout the span of his tumultuous relationships with his muses, there was always speculation and theory of abuse, whether this is physical or emotional. While it is difficult to distinguish which for either circumstance, we have the account of Gilot to confirm that any entanglement with the artists was far from sublime.

Read: Who Was Jackson Pollock?

Misogynistic Depiction of Women by Picasso

From the accounts we have of Picasso as a romantic partner, it’s not far to assume that Picasso had a slew of miserable relationships. Fueled by infidelity and manipulation, Picasso followed a trend in his relationships that was reflected in his art.

During the beginning of any relationship, he depicted graceful and intimate portraits — that were followed by melancholic to distorted compositions in the end.

Ballet Russes

During World War I, Picasso worked in Rome, where he met his first wife Olga Khokhlova, a Russian ballet dancer. Olga dominated his paintings from 1917 through the 1920s. In this period, Neoclassical images were challenged by Cubist abstractions.

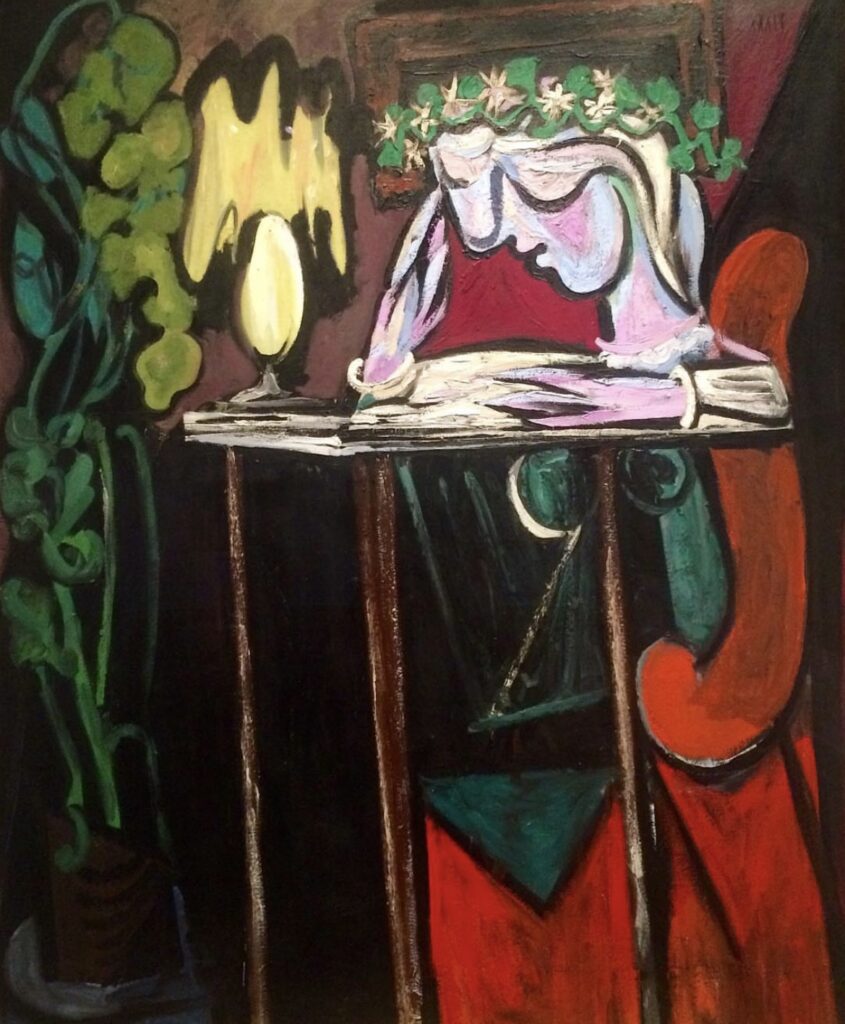

During the beginning of their relationship, Olga’s portraits are gracefully drawn and delicately colored. She would later be painted melancholic, often sitting or reading, and aloof. One can assume this was the effect of their relationship when Picasso began his affair with the younger Marie-Thérèse Walter.

By the end of their tumultuous marriage, which coincides with the launch of his relationship with Walter, these classically inspired portraits are gone. Now, Olga has a skull-like head with jaws. Her image emerges from mechanical and animal forms, as in Seated Bather of 1930. Picasso even referred to Olga as “the castrator.”

Though he took many lovers during the course of their relationship, the marriage was not officially recognized as being over until Khokhlova’s death in 1955. Olga filed for divorce once she discovered the affair between Picasso and Walter. However, Picasso did not want to divide his assets and refused the divorce, opting for an informal separation. Khlokhova was then kept in an abusive marriage and denied the rights she deserved for their separation.

The Younger Woman

The next phase of Picasso’s work was a series of highly erotic paintings that Picasso produced in a house he bought in Boisgeloup. His inspiration was Marie-Thérèse Walter. Picasso was now fifty, and Marie was twenty-nine years his junior.

During his unhappy marriage with Olga, Marie gave Picasso a new sexual and artistic lease on life. In such paintings as Siesta (1932) and Recumbent Nude (1932), Marie’s sleeping form is painted in voluptuous sweeping curves and flat areas of bright colors.

The somewhat later Nude in a Garden (1934) is described as one of the ultimate artistic expressions of sexual joy. Her body is abstracted and rearranged according to his desire, becoming a series of delicately painted pink breasts and orifices.

Surrealism advocated the reconstruction of one’s imaginative fantasies, and for Picasso, these fantasies were often of a sexual nature. This leaves a result of hybrid and often playfully erotic creatures in their own right.

Walter had one daughter with Picasso, Maya, whom he financially supported throughout his lifetime but never offered more in the relationship. Walter ultimately committed suicide in 1977, four years after Picasso had passed. It’s possible that the ongoing relationship and callousness toward Walter and their daughter led to Walter taking her life.

The Introduction of Dora Maar

The “Marie-Thérèse Walter era,” representing Picasso’s art during the late ’20s and early ’30s, ended when he met the surrealist photographer Dora Maar in l936.

Because these relationships overlapped, there are multiple sets of portraits depicting both women in the same pose that Picasso painted. Although they are in similar reclining poses, in the same setting, and on canvases of the exact dimensions, they expose Picasso’s dissimilar feelings toward the women.

While Marie-Thérèse Walter is depicted with a tender expression with her almond-shaped blue eyes as the dominant element in her face, the seductive Maar has an exotic conflicted face exaggerated by the heavy makeup, and her body is composed of cubist forms in these paintings.

As in the previous trends of Picasso’s relationships with women, the first portraits of Dora Maar are intimate and elicit Picasso’s desire and devotion to her. What would come later, we can assume, is just the pattern repeating itself.

The Weeping Woman

In Picasso’s later works during their relationship, Dora’s dark features are consistently depicted in acidic colors, and the cubistic and surrealistic forms emphasize her anguish. Connected to the history of Guernica, the works from Dora’s cycle are, for many Picasso scholars, one of the greatest moments of his oeuvre. Unlike the portraits of Marie-Thérèse Walter, those of Dora display intense emotion and turbulence.

A fragmented woman replaces sexual desire and pleasure with a tormented expression. For Picasso, she was “the weeping woman.”

The last painting Picasso did of Dora Maar, Portrait of Dora Maar, differs from all others in its realism and glowing austerity. He was enthralled by the Spanish Civil War and saw the pain and anguish of such times in Dora; this is an association she was displeased with and felt did not reflect her true nature.

One factor that separates Dora Maar from the rest of Picasso’s women is that she was also a successful painter and had a photographic style that earned her recognition. One of her most famous works, the self-portrait Weeping Woman, was painted in the surrealist style, probably around the time she and Picasso broke off their relationship.

The Fellow Artist

In 1943, Picasso met his next love, the artist Francoise Gilot. Francoise would be the only woman to leave him, after she bore him two children, Claude and Paloma.

The overall feeling transmitted by Picasso’s paintings of her is of independence. She carries a particularly unemotional gaze in her large eyes, and her full mouth is usually heavily outlined.

The erotic works during this period, when Picasso was now at the peak of his fame, often reflect an increasing awareness of his own mortality and the waning of his sexual powers. Picasso was 62 when they met, and Francoise was only 21. This age difference perhaps ignited some feelings of insecurity in his ability as a lover for a younger woman and provided him with constant reminders that his own youth was gone.

Long after their breakup, Gilot wrote a book, Life with Picasso, published in 1964 despite opposition from Picasso.

Gilot depicts Picasso as a man with an imperial ego who often made the women in his life victims or martyrs. “Pablo’s many stories and reminiscences about Olga and Marie-Thérèse and Dora Maar,” she wrote, “as well as their continuous presence just offstage in our own life together, gradually made me realize that he had a kind of Bluebeard complex that made him want to cut off the heads of all the women he had collected in his little private museum.”

Read: Highest Selling Paintings By Female Artists

The Second Wife

After the passing of Picasso’s first wife, Olga, he met a young Jacqueline Roque and married her in 1961. Their romance followed a similar trajectory to his previous muses. He charmed the young Roque at Madoura Pottery when she was 46 years his junior.

There are more portraits of her than of anyone else in Picasso’s work. In Picasso’s last works, the contours are often jagged, and the paint is thick and applied with particular urgency.

Picasso’s last work was a nude of a grotesquely aged woman, with sagging breasts and elephantine legs, slumped against the wall. She gazes at us with one broad, staring eye, while below, like a second eye, are the slashing lines of her genitals.

In his last years, he said, “I think about Death all the time. She is the only woman who never leaves me.” This is most likely related to Roque and her almost blindly loyalty to the artist. Unlike the other women in Picasso’s life, Roque silently obeyed and accepted the speculated abuse.

After Picasso’s passing in 1973, Roque was left as a benefactor of his estate and his children from previous relationships. Jacqueline was cold to the children, perhaps finally allowing her true feelings about her late husband’s extracurricular activities to surface.

In 1986, Jacqueline Roque shot herself in her Mougins home. She was 59 years of age and now the second of Picasso’s lovers to commit suicide.

Final Thoughts

Pablo Picasso has been dubbed a creative genius by historians and his peers, yet his “genius” heavily involved the women he abused and then ridiculed in his own art. The violence he enacted upon them is painted on the canvas.

It’s too convenient for established male artists to brush off their misogynistic abuses with their accomplished careers. For Picasso it’s possible that without these women and his relationships with them, we would never have had art in his distinct style. That being said, no art, no matter how great, can justify abuse or misogyny.

So maybe it is not possible to separate the art from the artist. If the art world truly strives to be inclusive, we should embrace the more complicated historical narratives that make up our art historical reality.