10 Times Famous Artworks Have Been Vandalized

What makes someone vandalize a precious artwork?

For some, it could be a political statement and a means of protest. Personal interest can also become a reason as for many young provocateurs who have targeted others’ artworks, sometimes as part of their own.

And others could be a call from a higher power or a self-fulfillment from the artist.

Below are ten iconic instances of art-world vandalism, from a call from God to climate protests.

Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus (1914)

The vandalism of famous artworks is often tied to significant political strife, as was the case when a suffragette vandalized by slashing Diego Velazques’s Rokeby Venus (1647-51) at London’s National Gallery.

Mary Richardson was moved to action by the arrest of Emmeline Pankhurst, a fellow suffragette who had been protesting at Buckingham Palace in an effort to get British women the right to vote.

Richardson, when asked about her reasoning for the attack, stated, “I have tried to destroy the picture of the most beautiful woman in mythological history as a protest against the government for destroying Mrs. Pankhurst, who is the most beautiful character in modern history.”

The ultimate damage done was a cut on Venus’ hip, however, it was enough to damage for the museum to close for two weeks during the restoration process.

Richardson was sentenced to a six-month prison sentence, during which she led a hunger strike resulting in the prison freeing her after no more than a few weeks.

Robert Rauschenberg Erased a de Kooning (1953)

In 1953, artist Robert Rauschenberg began a project that would involve vandalizing a preexisting artwork by erasing, and creating a new one in the process. He tried it first with his own drawings but found it a failed experiment.

Rauschenberg then approached Willem de Kooning, a celebrated Abstract Expressionist painter, asking for a work of art he could destroy. De Kooning reluctantly agreed and provided a drawing that was densely worked on.

Rauschenberg worked for months to erase the drawing using a variety of different erasers until de Kooning’s drawing was faded and almost unrecognizable.

The work is now held in the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art collection and is recognized as an example of Neo-Dadaist conceptual artwork.

Michelangelo’s Pietà Vandalized (1972)

Laszlo Toth, an unemployed geologist, walked into the chapel on Pentecost Sunday 1972 and vandalized Michelangelo’s Pietà using a geologist hammer, shouting, “I am Jesus Christ; I have risen from the dead!”

With 12 blows, he removed Mary’s arm at the elbow and knocked off her nose.

After the attack, the Vatican Museum undertook a painstaking 10-month-long restoration process in which restorers reassembled her arm and nose. Ultimately, the piece was restored and then exhibited behind bulletproof glass.

As for Toth, he was deemed mentally unstable by a Roman court and placed in the custody of a mental hospital, then released two years later and deported from Italy to Australia, his home country.

The 1974 Mona Lisa Attack

Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa can not elude vandalism attempts. In the past 110 years alone, she has been stolen, hit with a teacup, nearly sliced, and most recently caked.

But by far the most memorable vandalism of the piece involved a Japanese woman named Tomoko Yonezu and a can of spray paint.

In 1974, the work had gone on your from the Louvre in Paris to the National Museum in Tokyo, which had instituted crowd control measures that many disability activists deemed discriminatory.

Enraged by what she believed was an instance of ableism, Yonezu attempted to spray paint the Mona Lisa. The attempt was largely unsuccessful because of the bulletproof glass placed following a previous vandalism attack.

Yonezu was made to pay 300,000 yen for damages, and the National Museum set aside a day when the disabled could pay a visit to the painting to help refute any other similar attempts.

Rembrandt’s The Night Watch Vandalized (1975)

In 1975, Rembrandt’s largest painting, The Night Watch (1642) was targeted by a man wielding a bread knife, saying he was sent from a higher power.

Teacher Wilhelmus de Rijk had been sent to Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum, he said by “the lord,“ who had ordered him to slice the painting.

Although guards had initially attempted to hold him back, a dramatic scene transpired when he successfully vandalized the painting and cut a foot-long piece from the painting.

Because the work was in such pristine condition before the attack, restorers at the museum were able to get the painting back to its original form after four years.

Art Student Seeks a Statement on Mondrian and Dufy (1996)

A Canadian art student, Jubal Brown, was on a mission to send a message to the world, wanting to subvert bourgeois culture. He did so in less than favorable tactics, with the climax occurring at the Museum of Modern art in New York.

Brown projectile vomited a blue substance on Piet Mondrian’s Composition With Red and Blue in November of 1996.

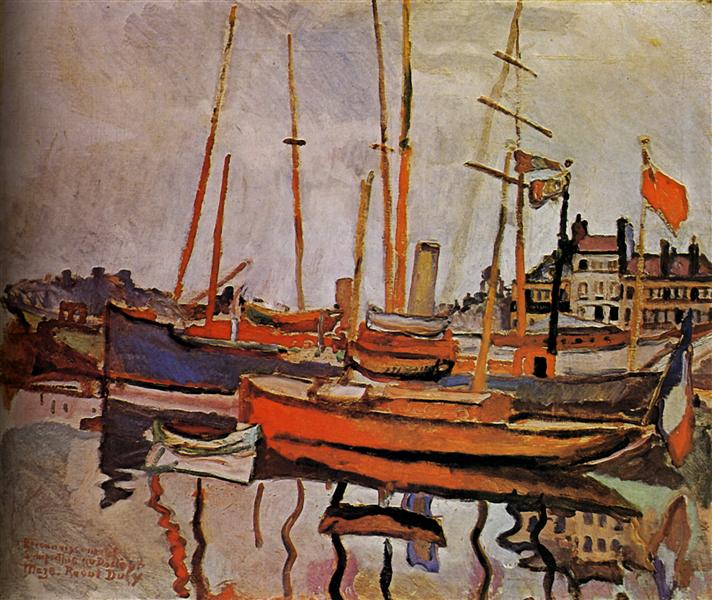

What is more surprising is that he had executed a similar demonstration months earlier. On May 15th, 1996, Brown entered the Art Gallery of Ontario and threw up red vomit on Raoul Dufy’s painting Harbor at le Havre after eating red gelatin and red cake icing.

Neither of the paintings was damaged, and both were successfully cleaned. The galleries initially believed that the incidents were accidental, but in early December 1996, Brown admitted that his actions were deliberate.

He said that they were part of a “performance art trilogy” entitled “Responding to Art” that targeted “oppressively trite and painfully banal” works. He said Harbor at le Havre “was just so boring it needed some color,” and he found Composition With Red and Blue “lifelessness threatening.”

Brown’s intention was to attack three paintings, each with one of the three primary colors: blue, red, and yellow, but, as far as we know, he never vandalized a third with yellow.

Political Messages Left on Picasso (2012)

In 2012, Houston art student Uriel Landeros vandalized a painting by spray painting a bull and Spanish word onto Pablo Picasso’s Woman in Red Armchair (1932). The word — Conquista, meaning conquer — seemed to confound most outlets that covered it at the time, especially since Landeros wasn’t immediately available to explain it.

He fled to Mexico, where he remained for six months, evading authorities in the United States. Ultimately, he was detained and given two years in prison.

It wasn’t until 2014, when he was released on parole, that he expounded on the political meaning of his message, which he said was a reference to the Conquistadors, Spanish and Portuguese settlers who led violent expeditions in Latin America centuries earlier.

Banksy, Self-Vandalized (2018)

The elusive street artist Banksy has long been known for showing unexpected art in unexpected places, but his most provocative gesture came up when he vandalized his own artwork.

The 2006 painting Girl With Balloon was up for auction in 2018 at Sotheby’s London, where it sold for $1.4 million. Seconds after the hammer came down; the painting appeared to slip through its frame and partially shred itself.

Whether the auction house had been made aware of the stunt in advance remained unclear as the room filled with gasps. The artist later admitted to the stunt through his social media, showcasing the behind-the-scenes of assembling the shredder within the frame of the painting.

Girl With Balloon now exists in its partially destroyed state as an entirely different artwork, which Banksy has titled Love is in the Bin. The work went on to sell for $25.3 million at Sotheby’s London in 2021.

Russian Guard Draws Eyes on Painting (2021)

In a turn of events, a museum staff member was the vandal behind this case.

In 2021 at the Yeltsin Center in Yekaterinburg, Russia a guard drew two eyes using a ballpoint pen on a group of faceless figures in a painting by Anna Leporskaya.

The mystery surrounding the case deepened when the museum waited two weeks to report the vandalism to the police. Initially, no charges were pressed. But by 2022, the guard, Aleksander Vasiliev, was charged with criminal vandalism and fined.

The story grew complex when Vasiliev gave an interview to E1 in which he discussed how his service had severely altered his mental and physical health in wars in Afghanistan and Chechnya.

He also claimed that a group of teens pressured him into vandalizing the work.

Environmentalists Target Museums (2022)

In 2022 climate activists began a series of protests in which they glued themselves to frames of iconic artworks as well as walls near the works across Europe, all in an attempt to move governments to act more speedily against ecological disaster.

These protestors took things to a new level when at the National Gallery in London during Frieze Week, two activists with Stop Oil vandalized a significant piece of the collection when they threw tomato soup on Vincent Van Gogh’s Sunflowers (1888).

Because the painting was under glass, it wasn’t damaged. The protestors have stated that their intent is to not harm the artwork, however, these acts have still brought a massive outcry led by conservatives for the environmentalists to halt.

Other similar protests came in its wake, including one in which mashed potatoes were tossed at a Monet in Germany and another in which oil was splashed across a Klimt in Vienna.

The most recent news in this series of vandalism is Just Stop Oil released a statement in which they stated that they may take things a step further, following in the footsteps of the Suffragette movement, and begin slashing the paintings.

The content is not intended to provide legal, tax, or investment advice. Past performance is not indicative of future performance. Investing involves risk. See important disclosures at masterworks.com/cd

*[Please note: All investing activities involve risks and art is no exception. Risks associated with investing through the Masterworks platform include the following: Your ability to trade or sell your shares is uncertain. Artwork may go down in value and may be sold at a loss. Artwork is an illiquid investment. Costs and fees will reduce returns. Investing in art is subject to numerous risks, including physical damage, market risks, economic risks and fraud. Masterworks has potential conflicts of interest and its interests may not always be aligned with your interests.

Liquidation timing is uncertain. Expenses and fees are listed in our Offering Circulars. Note: Fees are 1.5% per annum (in equity), 20% profit share, and certain expenses are allocated to the investment vehicle. Investors should review the offering circular for a particular offering to learn more about fees and expenses associated with investing in offerings sponsored by Masterworks. Masterworks will receive an upfront payment, or “Expense Allocation” which is intended to be a fixed non-recurring expense allocation for (i) financing commitments, (ii) Masterworks’ sourcing the Artwork of a series, (iii) all research, data analysis, condition reports, appraisal, due diligence, travel, currency conversion and legal services to acquire the Artwork of a series and (iv) the use of the Masterworks Platform and Masterworks intellectual property. No other expenses associated with the organization of the Company, any series offering or the purchase and securitization of the Artwork will be paid, directly or indirectly, by the Company, any series or investors in any series offering. For more information, see “IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES” at Masterworks.com/cd

This post was sponsored by Masterworks