Case Closed: The Saga of The Stolen de Kooning

On Thanksgiving day, 1985, Abstract Expressionist Willem de Kooning’s painting was cut from its frame and stolen in broad daylight from the University of Arizona Museum of Art.

For 37 years, the painting remained missing, and its status was considered a mystery.

But in October of 2022, Woman-Ochre returned home to the same gallery it hung in almost 40 years ago.

The tale of the theft will ring through the art world for years to come, as will the return of the painting. It goes:

A couple walked into the UAMA and, while the woman distracted the only employee working, the man cut Woman-Ochre from its frame, tore it from its backing, rolled it up, and walked out.

The whole heist took 15 minutes.

History of Woman-Ochre at UAMA

The painting has been in the center of the international spotlight due to its return to the University of Arizona Museum of Art more than three decades after it was stolen, but the work had an equally illustrious history before the theft.

Woman-Ochre was actually a late addition to the Woman series for which de Kooning is so well known. As one of the better-known artists from the Abstract Expressionist movement, which emerged in New York in the 1940s, de Kooning’s work — specifically, his Woman series — is regarded as one of most significant works of the era, and is now regarded as a canonical point of modern art.

The painting was one of the centerpieces of a substantial art donation made to the University of Arizona Museum of Art by Baltimore businessman Edward Gallagher Jr., as a memorial to his son Edward Gallagher III, who passed at the young age of 13.

The collection contains nearly 200 artworks donated between 1954 and 1978, including pieces from Post-Modern and Contemporary giants such as Jackson Pollock, Helen Frankenthaler and Franz Kline.

Who Stole Woman-Ochre?

The purported thieves of Woman Ochre are Rita and Jerry Atler.

The two seemed like a normal couple living in New Mexico. Rita was a retired speech pathologist, and Jerry was a retired music teacher.

The only link between the painting and the couple is that it was found hanging behind their bedroom door in 2017.

The Theory Behind Rita and Jerry Atler

The couple themselves became the center of of speculation and conspiracy around their extravagant lifestyle.

The couple was able to travel to 140 countries on public school teaching salaries, and they had over $1 million in their joint account at the time of their deaths, according to Danny Udero of the Silver City Sun News. This led to speculation that the unassuming couple were actually masterful art thieves, peddling their scores on the black market or through shady deals.

Although that theory has not been proven, the evidence stacked against the Atlers is astonishing in the case of Woman-Ochre.

Jerry passed in 2012, and Rita in 2017. With no family to come and separate their belongings in a will, their estate was auctioned off.

Antique dealer David Van Auker acquired the contents of the Alter’s house for $2,000, and the painting was found hanging on the back of the bedroom door. Unsuspecting of its real worth and value, Auker placed it in his Silver City, New Mexico store.

Numerous customers told him they thought it was a real de Kooning — a theory seemingly backed by a 2015 Arizona Republic article about the theft that the dealer found on Google. Concerned he had purchased a stolen painting, Van Auker contacted the University of Arizona Museum of Art, which dispatched a team to authenticate the painting and bring it back to Tucson.

Aside from that circumstantial evidence, there’s more to support the claim that the couple were thieves.

A picture of the Atlers at a 1985 Thanksgiving dinner in Tucson, Arizona, placed them in the same city as the de Kooning painting the day before it was stolen.

The couple had never been formally linked to the theft of the artwork by the University of Arizona Museum of Art, but according to a statement from the university, a man and woman entered the museum around 9 am November 29th, 1985. While the woman spoke to a security guard, the man went up to the second floor, where he cut the de Kooning from its frame, rolled it up, and hid it under a garment. The pair quickly left the museum some 15 minutes later with the stolen painting in tow.

Though the museum had no surveillance cameras and the thieves left no fingerprints at the scene, a fair amount of circumstantial evidence links the couple to the crime.

The Ateliers resembled a composite sketch of the thieves, specifically that Rita owned a red coat that looked like the one the woman thief donned. The couple drove a red sports car similar to the thieves’ getaway vehicle.

Lacking solid leads two years after the theft, the FBI added Woman-Ochre to its list of most wanted stolen artworks.

The painting was suspected of remaining in possession of the couple in their New Mexico home for the rest of their lives.

Woman-Ochre: The Missing Woman

Originally completed in 1961 as part of de Kooning’s Woman Series, Woman-Ochre was valued at $400,000 at the time of its theft and today is estimated to be worth around $100 million, according to the Getty.

Initially beginning in 1950, the Woman Series owes much to Pablo Picasso, and his depiction of the female form in his artwork. The female form likewise fascinated de Kooning, especially in his research of ritual sculptures and historical works of rounded women that were seen as early fertility symbols.

An example of the ancient artwork that de Kooning drew inspiration from is the Venus of Willendorf, a nearly 30,000-year-old figurine discovered over 100 years ago in an Austrian Village.

De Kooning’s women were stylistically different from his more figurative work of the 1940s, incorporating harsh lines and expressive brushstrokes. This would later be referred to as “action painting.”

Art critic Harold Rosenberg coined the term action painting in 1952. An alternative to Abstract Expressionism, action painting emphasized the revolutionary nature of the artist’s decision to paint. The artworks that used action painting could have been more perfect, with hurried, frenzied brushstrokes and paint spilling on the canvas. The work is deliberate but indelicate, incorporating painting techniques different from the traditional hand and wrist. In Woman-Ochre, de Kooning elegantly displays the vigorous brushwork that was a staple of his art, while highlighting his meticulous approach.

Other works from the woman series are housed in the Museum of Modern Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Whitney Museum, among other institutions.

What Conservation Efforts Were Necessary for Woman-Ochre

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York).

When the painting was recovered from the Silver City Antiques shop, it was found to be in a harsh condition and was then sent to the Getty Institute for conservation.

Interim Director of Current Exhibitions Olivia Miller shed some light on the realities of the conservation matter in an exclusive conversation with Masterworks Insights.

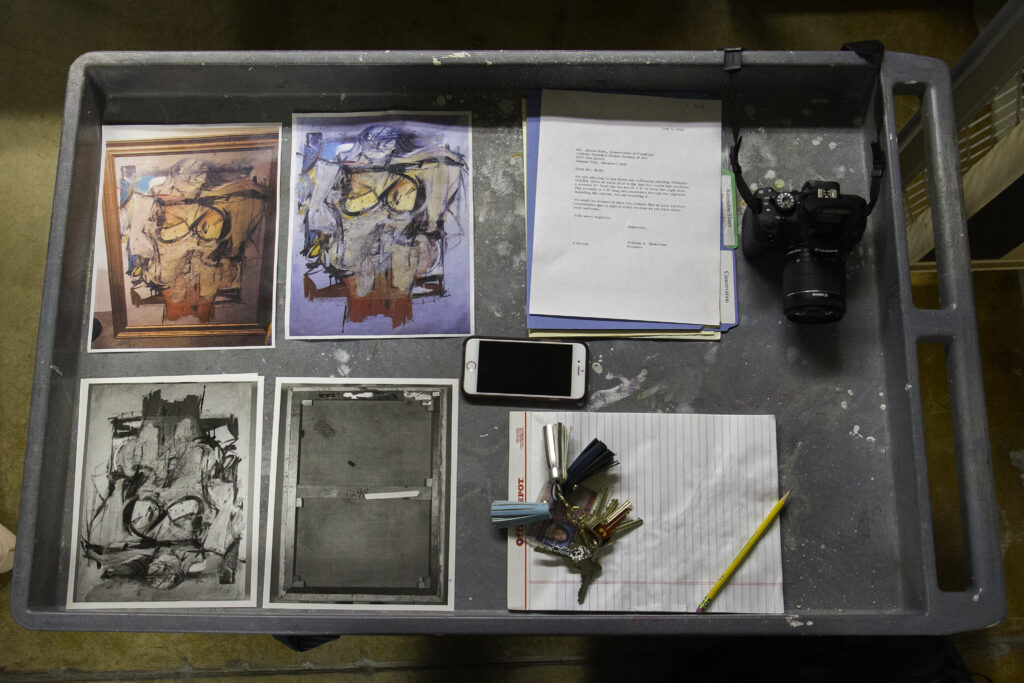

“The painting was in terrible condition when it was sent to the Getty. It spent 2 ½ years there undergoing scientific analysis and conservation treatment. This first involved copious amounts of research and documentation — photography of various kinds, scans, elemental mapping, paint sampling, etc.

“There were four main areas of conservation treatment, including paint consolidation, removing the varnish layers, inpainting, and reattaching the canvas to its original tacking margins left behind in the theft.

“The paint consolidation was probably the most time-consuming and challenging part of the treatment. The painting had been lined with a secondary canvas in a 1974 conservation treatment. The thief did not realize he needed to cut through both canvases — so instead, he ended up peeling Woman-Ochre from that lining canvas.

“That peeling (and the subsequent rolling up of the canvas) caused an enormous amount of lifting paint and paint loss that had to be repaired. The folks at the Getty did an amazing job and we are so thankful that they took on this complex project.”

The Return of Woman-Ochre

(Credit: Chris Richards, University of Arizona).

On October 22, 2022, the painting made its journey from Los Angeles back to Tucson for the final leg of its journey home.

The semi that brought Woman-Ochre from the Getty was met by museum staff with joy and excitement on the return of the painting.

Miller added, “We are absolutely overjoyed to have it back at the museum. It is rare for stolen artwork to be recovered, so we feel incredibly fortunate.”

“When we think back on the donor’s intent, giving the painting as a way to cope with the grief of losing his only child, Woman-Ochre’s absence was a harrowing one. It was stolen in 1985 and returned to a 21st-century museum. So much has changed in the art world and on our university’s campus in that time.”

“Right now, people are very interested in theft, recovery, and conservation (and rightly so!), but we also hope that people will again focus on it as an art object open to myriad interpretations.”

The painting now hangs on the second-floor gallery space of the Museum and is greeted by visitors, faculty, and students daily.

The significance that Woman-Ochre now conveys is not just as an example of an artist’s prime, but also as a relic of determination and the value held in art. The work was a missing masterpiece that had found its way back into its original hands, which are relatively unheard of among the other art heists of history, such as the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum.

There is no question that Woman-Ochre will remain a significant talking point of art history beyond the scope of its creator.

Invest in Pieces of Art History with Masterworks

If you would like to add a piece of art history to your investment portfolio, then you’re in luck.

Masterworks is an art investing platform that lets you invest in shares of multi-million dollar works by legendary artists like Ed Ruscha, Pablo Picasso, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Banksy and more.

With prices starting at $20 per share, investing in your favorite artworks has never been easier.

Here’s how Masterworks operates:

- The team researches artists whose works have the potential to increase in value.

- Masterworks buys less than 5% of the artwork they are offered.

- Masterworks securitizes and offers the artwork to investors.

- You can buy and sell shares on the secondary market or wait until the painting is sold to receive returns if the piece sells at a profit.

Simply head to Masterworks and submit your membership application now.

See important Reg A disclosures: Masterworks.com/cd