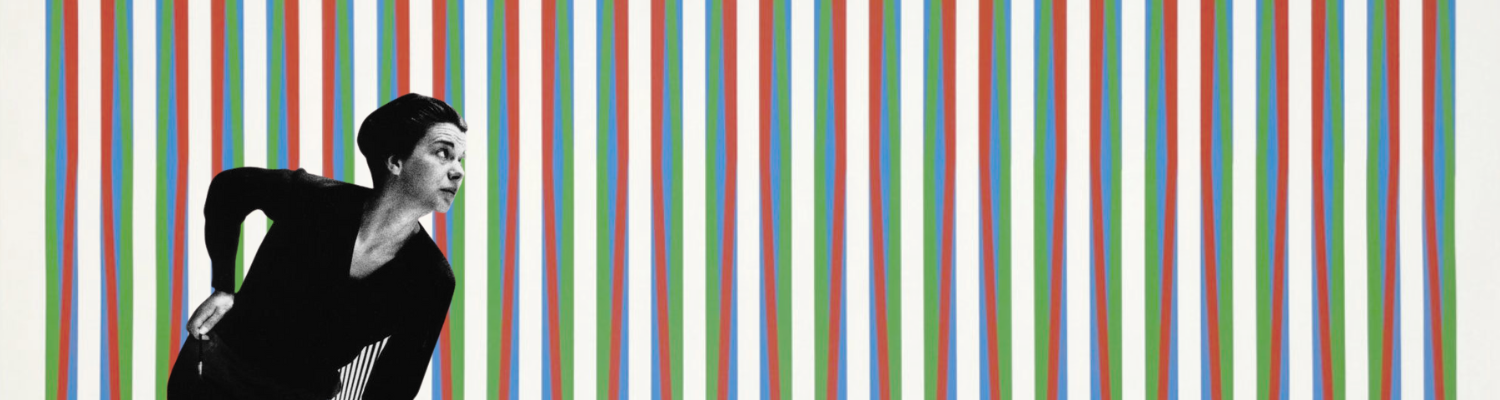

Who Is Bridget Riley: The Artist That Hypnotized The World

Almost synonymous with the Op Art movement for her distinctive black and white paintings, Bridget Riley far exceeded the boundaries of purely Optical Art.

Her works, governed by geometrical forms and structural shapes such as ovals, squares, parallel stripes and curves, create immersive environments where viewers are perceptually involved through optical illusions.

Bridget Riley’s work evokes sensations of movement that produce physical, psychological and emotional reactions associated with psychedelic effects; they are a bolt of color challenging the notion of the mind-body duality.

Biography of Bridget Riley

Bridget Riley was born on 24 April 1931 in Norwood, London.

Her father, John Fisher Riley, was a printer and owned his own business. He relocated his firm and the family to Lincolnshire in 1938 and when the Second World War broke out a year later, he was drafted into the army. While on active duty, he was captured by the Japanese and forced to work on the Siamese railway. He survived, but Riley remembers he was never the same. She recalls how “he had learned to live in a self-contained way, to isolate himself from what was around him.”

During the war years, Riley and her mother, sister and aunt lived in Cornwall, near the seaside town of Padstow. While she was there, she was given a great deal of freedom.

Later she would claim that these early experiences roaming the countryside, spending hours watching cloud formations and the shifting light throughout the day, strongly informed her artistic practice.

Early Training

After attending secondary school at Cheltenham Ladies College, she studied first at Goldsmiths’ College at the University of London (1949-1952), and then at the Royal College of Art, also in London, where she graduated with a BA in 1955. While there, she met fellow students Peter Blake and Frank Auerbach.

Being exposed to the London art scene for the first time, Riley found her studies at the Royal College of Art difficult, and she faced the dilemma many modern painters also experienced: “What should I paint, and how should I paint it?”

After leaving college, Riley returned to Lincolnshire to care for her father, who was suffering from injuries sustained in a car accident. While there, she underwent a physical and mental breakdown.

She returned to Cornwall in an attempt to recuperate, but the stay did little to revive her health. After returning to London in 1956, she was hospitalized for six months. During this period her artistic productivity diminished along with her health.

Mature Period

In 1956, Riley saw a vital exhibition of American Abstract Expressionist painters at London’s Tate Gallery. She returned to painting seriously again, exploring the lessons of Henri Matisse and Pierre Bonnard. The following year she was sufficiently recovered to take a job teaching art at a girls’ school in Harrow, near London.

Two years later, in 1958, she left teaching to become a commercial illustrator. That year, visiting an exhibition on The Developing Process, she became interested in the ideas of Harry Thurbon, a teacher at the Leeds School of Art.

Thurbon was a proponent of a new form of arts education that moved away from romantic ideas of expression toward concrete skills, embracing a connection to professional contexts, such as illustration and design. Thurbon’s ideas echoed the much earlier ideas of form and function taught at the Bauhaus, which was an important inspiration in early Op Art.

Riley attended Thurbon’s well-known summer school in Norfolk, where she met influential artist, writer and educator Maurice de Sausmarez. The pair began an intense relationship, and with de Sausmarez acting as her mentor, Riley began to expand her knowledge of the history of art and culture.

The 1960s

In 1960, the couple traveled to Italy, where Riley painted the countryside and took in the art of the Futurists. She was especially fascinated by the paintings of Boccioni and Balla, as well as the frescoes of Pierro della Francesca, and the black and white Romanesque facades found on the churches of Ravenna and Pisa.

On her return to London, Riley synthesized her experiences into her first geometric patterned paintings. She continued to develop this new, bold abstract style over the next year.

In 1962, in a legendary bit of luck, she took shelter from a sudden rainstorm in Victor Musgrave’s London gallery, and he offered her a show. This first exhibition met with great critical acclaim, and over the following decade, she was included in many of the well-known survey shows that came to define British painting in the sixties, including the 1963 “New Generation” exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery, London, with artists such as Allen Jones and David Hockney.

In 1965, Riley made her debut in the United States with a sold-out solo show at the Richard Feigen Gallery and a prominent place in the Museum of Modern Art in New York at their influential exhibition of Op Art, The Responsive Eye. Unfortunately, this rapid success led to one of the more difficult moments in her career.

In later accounts, Riley recalled her drive from the airport to the museum, passing shop window after window with dresses whose fabrics were inspired by Op Art or, in some cases, taken directly from her Op Art paintings. Despite the affinity between many Op Art artists and the textile and design industries, she was dismayed by the commercialization of her work and claimed: “The whole thing had spread everywhere even before I touched down at the airport.”

She tried to sue the designers of one of the dresses but was unsuccessful. Riley said at the time that “it will take at least 20 years before anyone looks at my paintings seriously again.”

Current Work

While Op Art’s critical acclaim suffered in the United States due to its rapid commercialization, Riley continued to enjoy success in Britain.

After 1967, Riley introduced color into her previously black-and-white paintings and has continued her explorations of form, color and space to the present.

In 1981, Riley traveled to Egypt. She was moved by the dynamic use of color in ancient Egyptian art, saying that “the colors are purer and more brilliant than any I had used before.” She was fascinated by the way Egyptian artists managed to use only a few colors to represent what she described as the “light-mirroring desert” around them. Her paintings after this trip contained a more accessible arrangement of colors than she had previously used and a palette inspired by the Egyptian art she had seen.

In the later 1980s and 1990s, Riley completed a number of large-scale, site-specific commissions. For example, in 1983 Riley painted a series of murals on the interior of the Royal Liverpool Hospital. The color scheme she chose was intended to make the patients calmer, and the murals significantly lowered the rates of vandalism and graffiti within the hospital.

Riley continues to produce art today. She works from several studios, including in her home in South Kensington, where four out of the five floors are dedicated to artistic production.

Op Art: Exploring Movement and Perception

Following a journey to Italy in 1960 with her mentor Maurice de Sausmarez, Riley began synthesizing her many influences into her first geometric patterned configurations. In her paintings, sequential elements are repeated to create a field of optical frequencies with the intention of semiotic conceptualism.

Her first exhibition at Victor Musgrave’s London gallery in 1962 brought her great critical acclaim and, three years later, she made her debut in the United States.

Her sudden success, however, was accompanied by the commercialization of her patterns, especially by the fashion world, and the appropriation of her work by popular culture. Riley saw this as contrasting with her idea of the social nature of art because of its engagement potential with the viewers.

In the later 1980s and 1990s, Riley created a number of large-scale, site-specific murals, including at the Tate Gallery of London and the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris and the National Gallery in London.

Artistic Style and Concepts

Heavily influenced by Neo-Impressionism — mainly through the work of Georges Seurat and other Impressionist painters, whose works she used as a tool to comprehend optical science — Riley progressively implemented her first pointillist experimentations with the study of color and contrast. This started the investigation of movement and perception, shifting into the realm of pure abstraction, which can be seen throughout her oeuvre.

The Process of Creation

Bridget Riley produced her first stripe painting in 1967, while she was still in the process of studying color and movement.

Some of her later works would portray different compositions, such as her tessellating patterns in the ’80s. She embraced them to develop her own variations, integrating the patterns into her signature geometrical expression.

Throughout her career, Bridget Riley seems to be constantly exploring the idea of creation as a concept rather than an action. Then again, the action derives as a natural outcome. In her words, “It’s a process of discovery.”

The Legacy of Bridget Riley

Bridget Riley became an icon, not just of Op Art, but of contemporary British painting in the 1960s. She was also the first woman to win the painting prize at the Venice Biennale in 1968.

Riley’s innovations in art inspired a generation of Op artists, including Richard Allen and Richard Anuszkiewicz. Due to the abstract geometric nature of much of her work, she has also been cited as an influence for many designers, including the well-known graphic designer Lance Wyman, whose work on the Mexico 1968 Olympic Games shows a strong correlation with Riley’s aesthetic.

Riley’s influence also had a hand in shaping the realm of Contemporary Art. She also had an impact on a diverse number of artists associated with the Young British Artists movement, including Damien Hirst and Rachel Whiteread. Even if artists aren’t influenced by her abstract style, they cite her intelligence and perseverance as a model in an ever-changing art world.

Most Famous Artworks by Bridget Riley

Artworks from Bridget Riley’s rich body of work are part of many prestigious collections around the world. Here is a selection of her most famous works.

Kiss

Simultaneously minimal and dramatic, Kiss is a seminal abstract painting by Riley and the earliest of her groundbreaking black and white paintings from the 1960s that has brought her international acclaim.

The contrasting, almost touching areas of black and white are sharply delineated and evoke, in pure abstraction, the feeling of two people just about to kiss and the feelings those performed actions would fire.

Movement in Squares

Bridget Riley described Movement in Squares as “something that happened on the paper that she had not anticipated.” This work is the ultimate result of years of experimentation and artistic research, which culminated in such an impressive precision of geometric forms and bending shapes generated almost by intuition.

The development of contrasts and optical illusions providing a sense of movement served as the beginning of Riley’s early investigations into the conceptual roles of geometric shapes.

Shadow Play

A master of optical illusions, Shadow Play by Bridget Riley is an exquisite visual trigger, where even figuring out the colors and counting them seems impossible.

In this piece lies a meticulous accumulation of two-dimensional shapes through elusive depth and repetitive geometric structures in a complex yet clear vertical and diagonal stripe structure. The signature colors in this painting are distinctive of the artist’s “Egyptian palette” — an outcome of her intense fascination from her 1981 trip to Egypt.

Riley was deeply impressed by the ability of Egyptian artists to use a limited color palette to represent what she defined as the “light-mirroring desert” surrounding them. The trip to Egypt represented a watershed in her artistic practice; following this experience, her paintings would contain a more accessible arrangement of colors.

Invest In Bridget Riley

If you are one that is fascinated by the optical illusions found in Bridget Riley’s paintings, you can now invest in fractional shares of some of her Op Art masterpieces with Masterworks.

Through Masterworks, you can easily invest in contemporary art valued at a few hundred thousand to tens of millions of dollars created by some of the world’s most celebrated artists.

How it Works

Here’s a quick rundown of the process:

- The team of researchers uses proprietary data to identify which artist markets may have momentum.

- The acquisition team then purchases the piece.

- Masterworks files an offering with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to securitize the art. This allows anyone to invest in shares of the art. You can then learn more about the artist’s market data and historical price appreciation to help pick an original artwork that appeals to you.

- Once you’ve invested, all that’s left to do is wait. Masterworks will generally hold a piece for 3 – 10 years. You receive a pro-rata share if the piece is sold at a profit.

- Alternatively, you can buy and sell your shares on the secondary market.

To get started, submit your membership application and set up a time for a quick call with a representative.

See important Reg A disclosures: Masterworks.com/cd