Understanding the De Stijl Art Movement

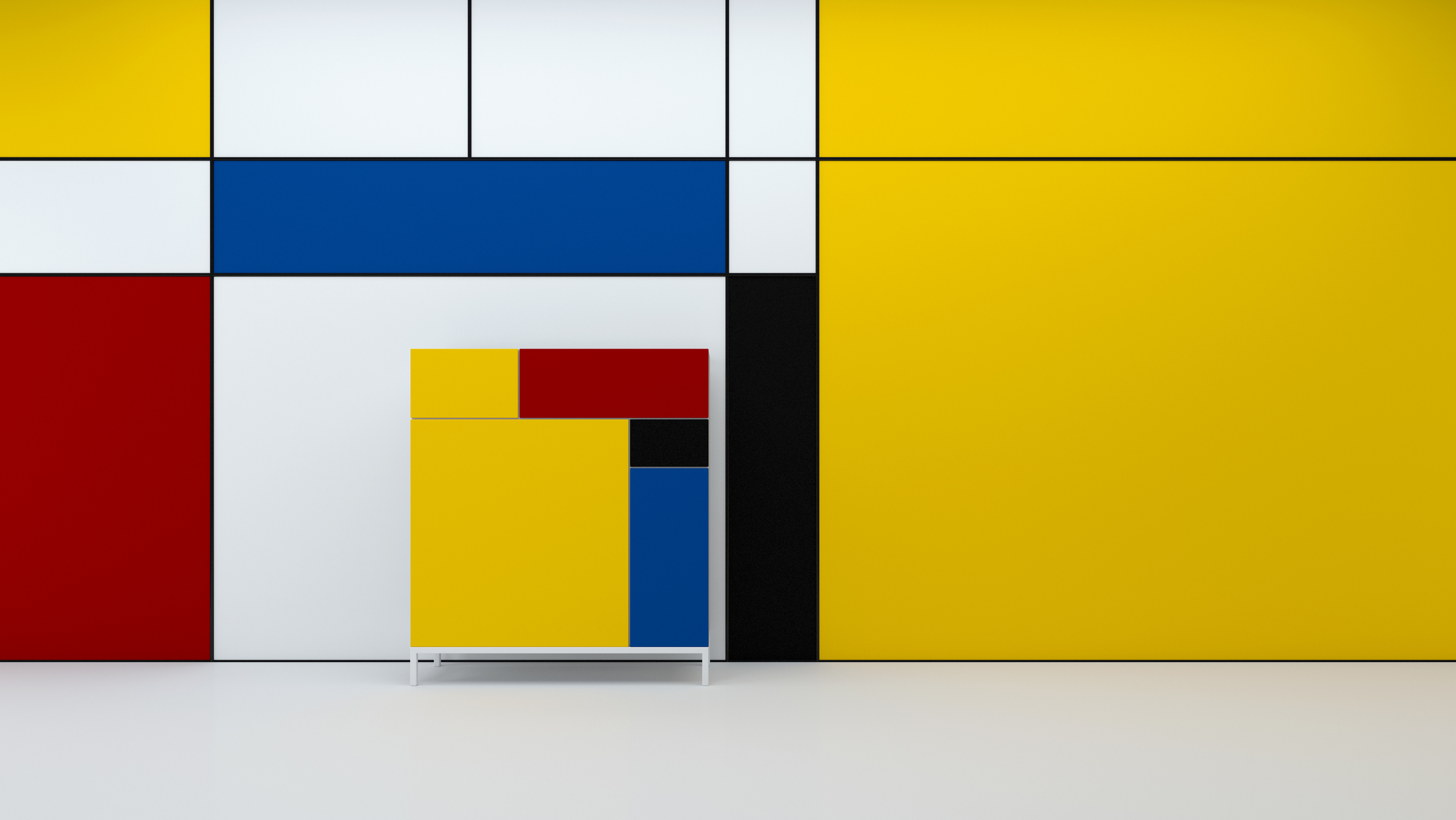

The Netherlands-based De Stijl movement embraced an abstract, pared-down aesthetic centered on basic visual elements such as geometric forms and primary colors.

Partly a reaction against the decorative excesses of Art Deco, the reduced appearance of De Stijl art was envisioned by its creators as a universal visual language for the modern era, a time of a new, spiritualized world order.

Led by the painters Theo van Doesburg and Piet Mondrian, its central and celebrated figures, De Stijl artists applied their style to various media in the fine and applied arts and beyond.

What Is the De Stijl Style?

Promoting their innovative ideas in their journal of the same name, the members envisioned nothing less than the ideal fusion of form and function, thereby making De Stijl the ultimate style.

To this end, De Stijl artists turned their attention not only to fine art media such as painting and sculpture but virtually all other art forms, including industrial design, typography, and even literature and music.

De Stijl’s influence was perhaps felt most noticeably in the realm of architecture, helping give rise to the International Style of the 1920s and 1930s.

History of De Stijl

In 1917, Theo van Doesburg founded the contemporary art journal De Stijl to recruit like-minded artists to form a new artistic collective that embraced an expansive notion of art infused by utopian ideals of spiritual harmony. The journal provided the basis of the De Stijl movement, a Dutch group of artists and architects whose other leading members included Piet Mondrian, J. J. P. Oud and Vilmos Huszar.

Adopting Cubism and Suprematism’s visual elements, the Dada’s anti-sentimentalism and the Neo-Platonic mathematical theory of M. H. J Schoenmaekers, a mystical ideology that articulated the concept of “ideal” geometric forms, the exponents of De Stijl aspired to be far more than mere visual artists.

At its core, De Stijl was designed to encompass a variety of artistic influences and media, its goal being the development of a new aesthetic that would be practiced not only in the fine and applied arts. Along with this the movement would also reverberate in a host of other art forms as well, among them architecture, urban planning, industrial design, typography, music and poetry.

The De Stijl aesthetic and vision were formulated in significant response to the unprecedented devastation of World War I. The movement’s members sought a means of expressing a sense of order and harmony in the new society that was to emerge in the wake of the war.

Key Ideas of De Stijl

Like other avant-garde movements of the time, De Stijl, which means simply “the style” in Dutch, emerged largely in response to the horrors of World War I and the wish to remake society in its aftermath.

Viewing art as a means of social and spiritual redemption, the members of De Stijl embraced a utopian vision of art and its transformative potential.

Among the pioneers of abstract art, De Stijl artists adopted a visual language consisting of precisely rendered geometric forms — usually straight lines, diagonal lines, squares, and rectangles — and primary colors. This was expressing the Dutch artists’ search for the universal, as the individual was losing its significance. This austere language was meant to reveal the laws governing the world’s harmony.

Even though De Stijl artists created work embodying the movement’s utopian vision, their realization that this vision was unattainable in the real world essentially brought about the group’s demise.

Ultimately, De Stijl’s continuing fame is primarily the result of the enduring achievement of its best-known member and true modern art master, Piet Mondrian.

Artists of De Stijl

Piet Mondrian

Recognized for the purity of his abstractions and methodical practice, Mondrian’s paintings emphasize the core ideals of the art movement. He radically simplified the elements of his paintings to reflect what he saw as the spiritual order underlying the visible world, creating a clear, universal aesthetic language within his canvases.

In his best-known paintings from the 1920s, Mondrian reduced his shapes to lines and rectangles and his palette to fundamental basics, pushing past references to the outside world toward pure abstraction.

Gerrit Rietveld

By the time architect Gerrit Rietveld opened his furniture workshop in 1917, he had taught himself drawing, painting, and model-making.

Rietveld is best known for designing his Red and Blue Chair in 1917, becoming an iconic piece of modern furniture. The chair perfectly reflects De Stijl’s concepts in the furniture design medium, incorporating simple horizontal lines and primary colors.

He is also known for building the Rietveld Schröder House in 1924 in close collaboration with the owner Truus Schröder-Schräder. The house was completed in Utrecht on the Prins Hendriklaan, and was designed to showcase that the ideals of De Stijl could be transferred to all media. The house has a conventional ground floor but is radical on the top floor, lacking fixed walls but instead relying on sliding walls to create and change living spaces.

Theo Van Doesburg

Van Doesburg created numerous abstract paintings and designed buildings, room decorations, stained glass, furniture and household items that exemplified De Stijl’s aesthetic theories and his ideas.

He wrote numerous essays and treatises on geometric abstraction and De Stijl, and organized many exhibitions of works by De Stijl artists and related movements.

Acting on his mission to inform people of the tenets of De Stijl, Van Doesburg abstracted the image of a grazing cow in Composition No VIII (The Cow). He began by creating figurative studies and gradually changed the image until the cow became a carefully coordinated arrangement of colorful rectangles and squares.

De Stijl Concepts and Themes

Pure Geometric Abstraction and De Stijl Visual Language

De Stijl was the first-ever journal devoted to abstraction in art, although the movement’s artists were not the first to practice abstract art. Other painters, perhaps most notably Wassily Kandinsky, Kazimir Malevich, and Hans Arp, had earlier created nonobjective art, often incorporating geometric forms in their work.

But the artists and architects associated with De Stijl — painters such as Mondrian, Van Doesburg, and Ilya Bolotowsky, and architects such as Gerrit Rietveld and J. J. P. Oud — adopted what they perceived to be a purer form of geometry, consisting of forms made up of straight lines and basic geometric shapes (rendered mainly in the three primary colors).

These motifs provided the fundamental elements of compositions that avoided symmetry and strove for a balanced relationship between surfaces and the distribution of colors.

Neo-Plasticism

Neo-Plasticism refers to the painting style and ideas developed by Piet Mondrian in 1917, promoted by De Stijl.

Denoting the “new plastic art,” or simply “new art,” the term embodies Mondrian’s vision of an ideal, abstract art form he felt was suited to the modern era.

Mondrian’s essay “Neo-Plasticism in Pictorial Art,” which set forth the principles of the concept, was published in twelve installments of the journal De Stijl in 1917-18. Mondrian described Neo-Plasticism as a reductive approach to artmaking that stripped away traditional elements of art, such as perspective and representation, utilizing only a series of primary colors and straight lines.

Mondrian envisioned that the principles of Neo-Plasticism would be transplanted from the medium of painting to other art forms, including architecture and design, providing the basis for the transformation of the human environment sought by De Stijl artists. In Mondrian’s words, a “pure plastic vision should build a new society, in the same way that in art it has built a new plastics.”

The concept of Neo-Plasticism was primarily inspired by M. H. J. Schoenmaekers’s treatise Beginselen der Beeldende Wiskunde (The Principles of Plastic Mathematics), which proposed that reality is composed of a series of opposing forces — among them the formal polarity of horizontal and vertical axes and the juxtaposition of primary colors.

Elementarism

While only horizontal lines and vertical lines were to be utilized in Neo-Plasticism, in 1925, van Doesburg developed Elementarism, which attempted to modify the dogmatic nature of the style by introducing the diagonal line, a form that for him connoted dynamism.

Prizing horizontal and vertical lines for their connotation of stability, Mondrian strongly disagreed with van Doesburg’s newfound emphasis on the diagonal — a disagreement that famously prompted Mondrian to secede from De Stijl shortly thereafter.

For Mondrian, van Doesburg’s introduction of the diagonal amounted to artistic heresy; in Mondrian’s view, the Elementalist diagonal repudiated De Stijl’s efforts to fully integrate all the elements of the painting by creating tension between the composition and the picture plane.

Later Developments of De Stijl

De Stijl-inspired architecture, particularly by Rietveld and Oud, was built in the Netherlands throughout the 1920s, all of which seemed to defy van Doesburg’s theory of Elementarism, instead utilizing clearly defined horizontal and vertical lines.

It also had a major influence on Bauhaus architecture and design; several members of De Stijl taught at the Bauhaus, perhaps most importantly van Doesburg, who lectured there from 1921-22.

The movement’s geometric visual language, along with its architectural concepts such as form following function and the emphasis on structural components, would reverberate in Bauhaus architectural practice, as well as the global idiom known as the “International Style.”

Beyond the realm of architecture, the pared-down De Stijl aesthetic influenced many subsequent artists and designers of the 20th century and beyond art history. Among them were the Abstract artists Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman, Hard-Edge painters Frank Stella and Frederick Hammersley, and Minimalists Donald Judd and Dan Flavin.