History of the First Modern Art Market

With the recent buzz and excitement over record-breaking auctions in the contemporary art market, it’s important to note how different the extravagant displays at auction are from their much more humble beginnings.

It leaves us to question what the earliest days of the modern art market were like. And how did it transform into this $1.7 trillion market today?

When Did the First Modern Art Market Form?

The first real free market economy for art occurred in the Dutch republic in the 1600s. This republic was the most wealthy and urbanized nation at the time.

Its wealth was based on local industries such as textiles and breweries and the domination of the global trade markets by the Dutch East India Company.

The earliest manifestation of the secondary art market — one in which artworks are resold and not purchased directly from their creator — can be traced back to the sixteenth century.

Dealers who traded in goods such as furniture or clothes often had paintings and sculptures on offer. As collecting and art appreciation grew in popularity, dealers began specializing in art sales, which gave rise to the profession of art dealer.

During the 17th century, collecting became a much more visible activity. It also became more specialized and less encyclopedic: the development of the gallery as a technical viewing or display area encouraged collectors to concentrate on paintings and sculptures rather than the acquisition of an omnium gatherum, or collection of miscellaneous things, of works of art and natural curiosities.

Thanks to the implementation of innovations such as printed catalogues containing detailed information about artists, art dealers soon took over the market, which until then had been dominated by artists’ workshops.

How Did The Dutch Establish The First Art Market?

Religious Influence

The Renaissance brought a new wave of interest in antiquity and art, giving birth to the first collections and patrons.

The epicenter of these changes was 15th Century Florence, where artists competed against each other to draw the attention of Aristocats and the church and gain their patronage. More generous patrons could even take their pupils into their households in exchange for providing them with works of art.

One of the era’s most potent and famous art supporters was the Catholic Church, which employed artists as great as Botticelli and Michelangelo.

It’s important to remember this unique Renaissance form of the early art market has to be classified as primary — works were being acquired directly from their makers, usually through commission.

However, due to the Protestant Reformation and the absence of liturgical painting in the Protestant Church, religious patronage was a less robust source of income for artists in Dutch society.

Rather than working on commission, artists then sold their paintings on an open market in bookstores, fairs, and through dealers.

Specialization of Subject Matter

In the Dutch Golden Age, the first open market led to the rise in five significant categories of painting: history painting, portraiture, scenes of everyday life or genre painting, landscapes, and still-life paintings. History or narrative paintings with biblical or allegorical themes were the most prized, expensive, and often largest in scale.

Old Testament stories were popular, such as those depicted by Jan Steen in Esther and Haman.

Still-life paintings became increasingly popular to collect because they tended to be less expensive and smaller, like Adriaen Coorte’s Gooseberries on a Table.

Without the financial security of commissions, many Dutch painters specialized in very specific categories, such as only painting night landscape paintings or flower still lives, which meant that artists could hone an individualized style and create a larger number of paintings within a trademark niche.

It has been estimated that between five and ten million works of art were produced during the century of the Golden Age of Dutch art. Very few of these, perhaps less than 1%, have survived.

According to art historian Madlyn Kahr, much of the increase of purchasing art came from aesthetic reasoning: “Works of art hung in almost all Dutch homes, from simple prints and copies to originals. In fact, pictures of some kind or another were found in about two-thirds of Dutch households.”

A Strong Middle Class

After the end of the 80-year war with Spain in 1648, the Netherlands had emerged as a vital new political, economic and cultural force. One of the consequences of the Republic’s independence was the change in the balance of power.

For the first time in modern history, power had passed into the hands of the bourgeois. This change was to have enormous repercussions on the art market, as economic power translated into a sizable urban middle class with disposable income to purchase art.

A considerable proportion of inhabitants of Dutch towns had more than sufficient income to provide for their fundamental needs. Many chose to spend their surplus on home furnishing, including pictures. This led to a great demand for paintings at low prices. Since these paintings were to be hung in ordinary Dutch house rooms, most were small.

One explanation for the Dutch desire for paintings relates to the population’s quintessential affection for their land and home.There was a sense of pride in displaying the landscapes of the Netherlands and the Seascapes of the coast in their home. Along with the natural beauty of the low countries, the Dutch were fond of supporting local artisans and artists, inviting a robust economy.

What Did the Early Art Market Look Like?

In the 17th-century Netherlands, paintings were sold in various styles, prices, and places.

Paintings could be bought directly from artists in their studios or from art dealers who had become the most important buyers of art.

Each dealer bought and sold works of different origins and at different prices. Some commissioned works of important Dutch artists such as Vermeer or Frans Hals for their best clients, and bolstered their stock by employing copyists who reproduced any masterpiece that was asked of them.

Some dealers sent printed illustrated catalogs to potential clients. Some painters were called upon to illustrate books or to invent decorative motifs for ceramic wares. This is widely considered to be one of the earliest examples of a modern auction catalog, a standard practice today.

Purchase For a Purpose

In the Netherlands, decorating the house with a variety of relatively inexpensive paintings, something neighboring Italian immigrants were already familiar with, caught on with the native population.

Second-generation immigrants took advantage of this profitable gap in the market and competed with the imports by producing paintings with similar techniques and subjects, but of a higher quality.

When previous purchasers were deceased, paintings that they had bought and hung in their houses found their way again into the open market through estate auctions that dealers attended.

Innkeepers, such as Vermeer’s own father, frequently dealt in paintings. Paintings were also sold at fairs and at lotteries organized for charitable organizations’ benefit.

Guilds

Artist Guilds also became increasingly popular in Dutch society. Dutch painters of the 17th century as well as printers, bookbinders, glassmakers, embroideries and sculptors were bound together in local trade organizations called the Guild of Saint Luke of Delft.

The Guild’s principal function was to regulate the commerce of artists and artisans, acting as checks and balances of the current art market. The guild would host its own auctions throughout the low countries of Europe.

Some famous artists that studied through the Guild were Rembrandt and Jan Van Goyen.

Prices were generally low for undistinguished works, because the competition among artists was fierce. On the lower range, paintings could be bought for a few guilders, on the upper range for 500 guilders, approximately half of the price of an average house. Painters trained in the Guild of Saint Luke had better chances of earning a respectable living.

What Came After the First Modern Art Market?

A hundred years later, Pierre Durand-Ruel (1831-1922), the owner of a Parisian gallery, took an interest in the then-unknown Impressionism. To promote this new movement, he began to present works by young, unknown artists among more established ones. He became the first art dealer to appreciate the avant-garde and promote young talents by covering all their costs and navigating their artistic development.

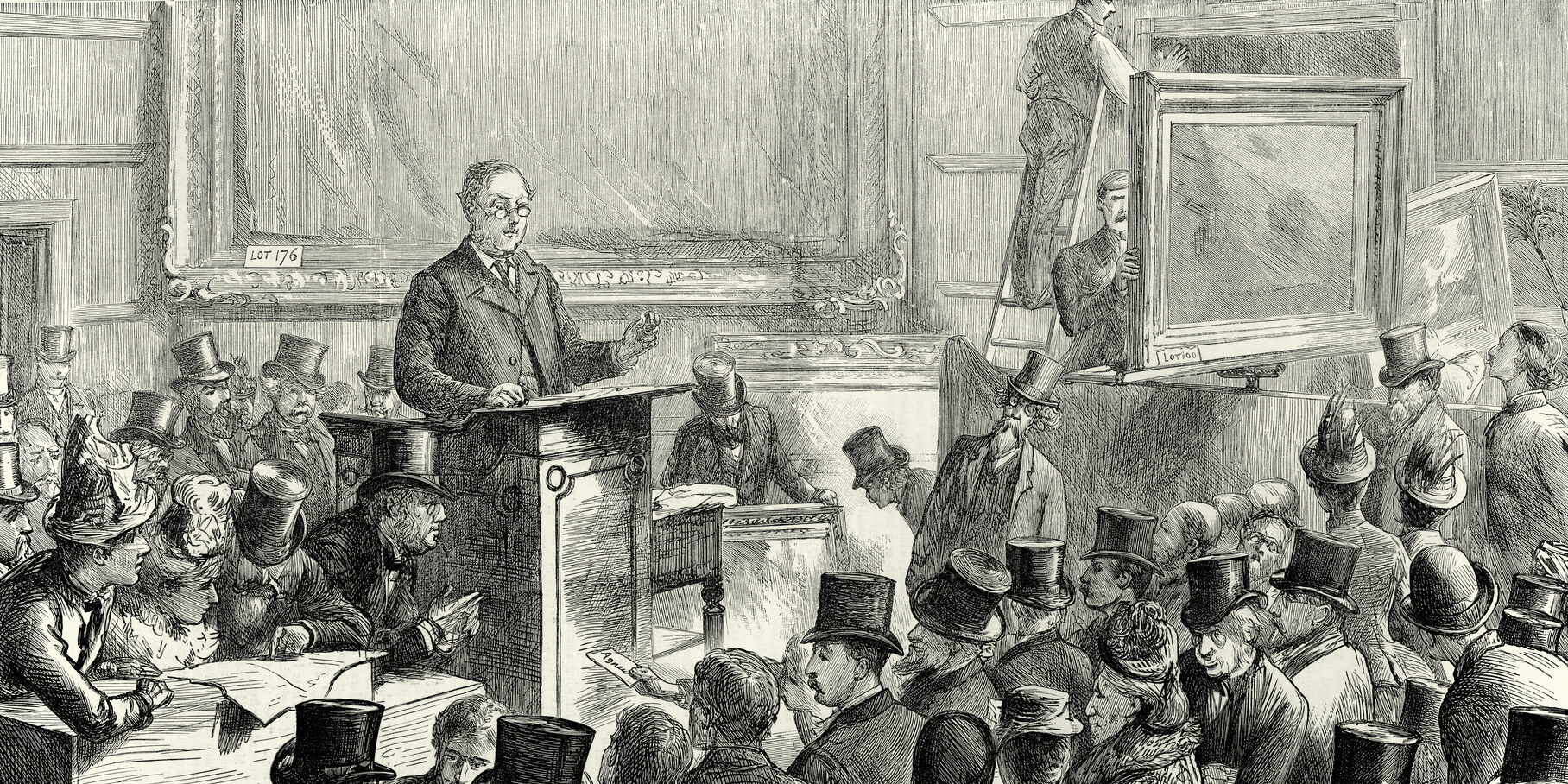

Around the eighteenth century, another important agent of the market entered the game. Sotheby’s and Christie’s, today the most recognizable auction houses in the world, were established in London. Initially, their area of focus was antiques, but with time both grew to open multiple departments and offices around the globe, dealing in art ranging from ancient to contemporary.

The Bottom Line

Today we can experience the art market at the peak of its development with its traditional agents and mechanisms developed through the ages still present.

Its evolution, however, is not complete and today, we can witness its shift toward the virtual world. Online auctions have become a standard practice and most commercial galleries offer their works online.

Every year, more portals specializing in online sales emerge, becoming a new force in the market.

One of these portals is the new concept of fractional Investing in art. This option is much more accessible than spending millions of dollars at auction for blue-chip art, as the modern art market seems to demand.

Masterworks is an art investment platform that lets you invest in shares of multi-million dollar artworks by artists such as Banksy, Andy Warhol, and Basquiat.

Get started by completing Masterworks’ membership form.