Frida Kahlo: The Life Story You May Not Know

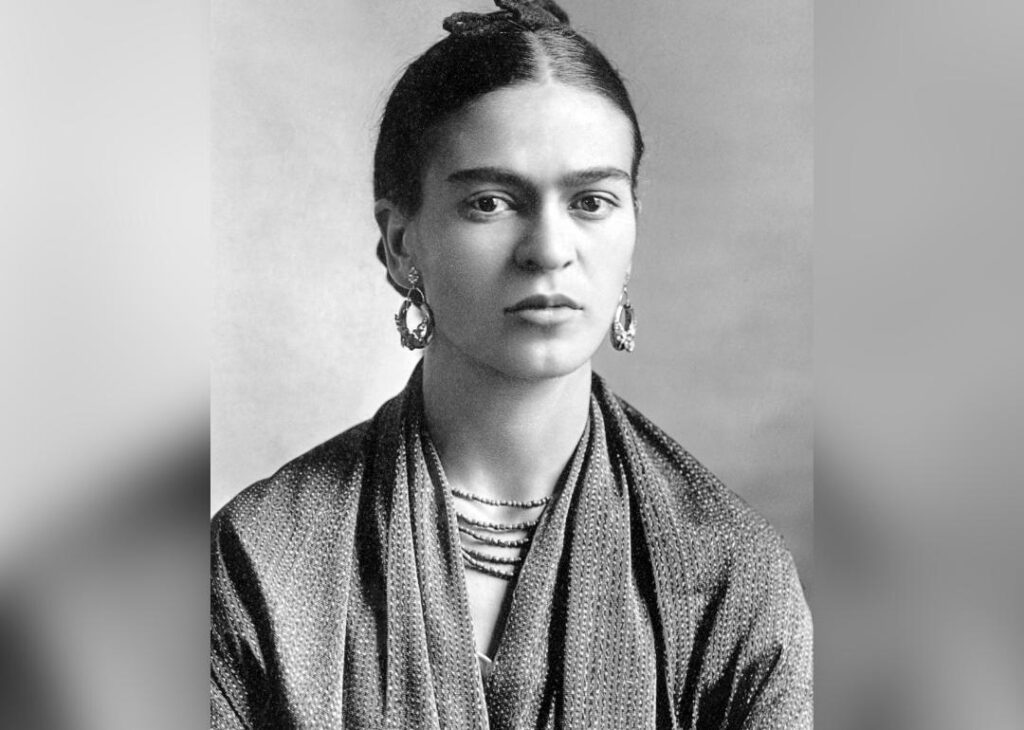

Frida Kahlo is among the most recognized artists of the 20th century. Her work encompasses everything from feminism and political discourse to deeply personal themes like love, pain, and suffering. In many ways, she was considered an icon for her modern views on female sexuality, the adversity she overcame, and how her pride in Mexican culture manifested in her artistry.

Kahlo’s impact is evident across the globe, in museums and popular culture alike. Exhibitions featuring her work have appeared in numerous cities worldwide, most recently in Chicago, Paris, New York, and Mexico City, with a “multi-sensory” exhibition set to open in Australia in 2023. Images of Kahlo are also popular sellers on t-shirts, mugs, backpacks, and wall art, and murals of her likeness decorate innumerable public art installations.

In 2021, one of her paintings, “Diego and I”—a depiction of her and husband and fellow artist Diego Rivera’s complicated relationship—sold for almost $35 million at Sotheby’s, making her the first Latin American—and only the second woman—to have a piece sell for so much. Kahlo’s work made even more recent headlines when one of her sketches from 1944, valued at $10 million, was publicly burned to promote the sale of nonfungible tokens based on the sketch.

Many sources nourished the wellspring of Kahlo’s artistic inspiration. In addition to her relationships and Mexican heritage, her work was heavily influenced by an almost fatal accident when she was 18, leaving her in acute physical pain for the rest of her life.

Masterworks compiled a list of significant life events and personality and art characteristics from different sources, including media outlets, scientific papers, and online encyclopedias.

Keep reading to find out about her roots, her tragic life story, and her legacy.

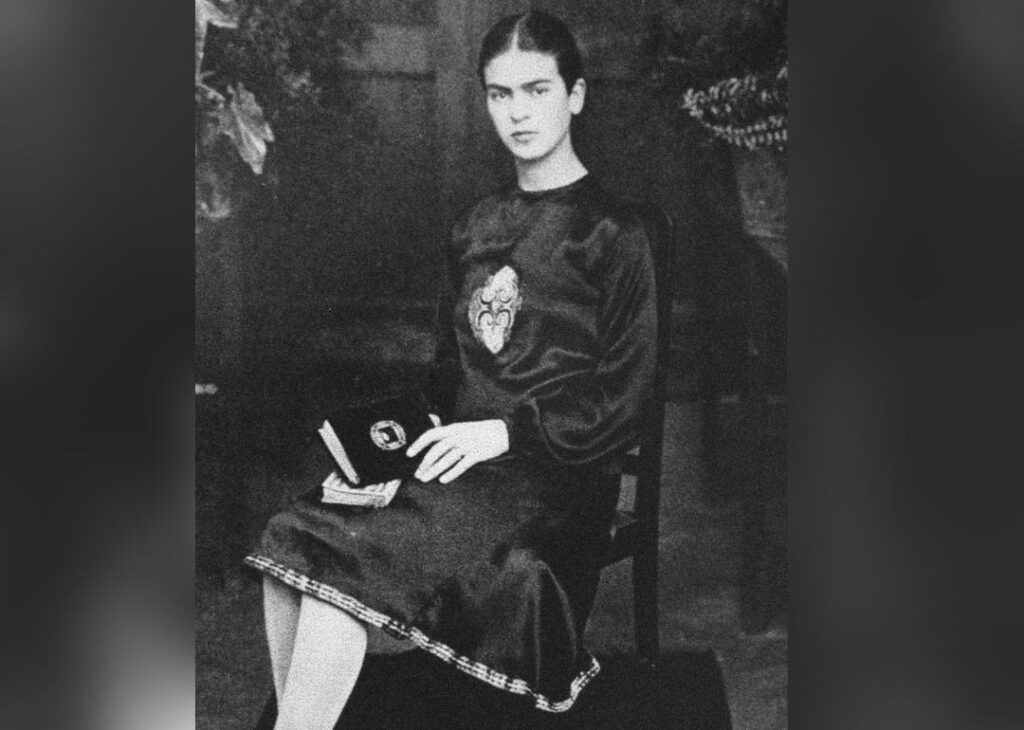

July 6, 1907: Born in Coyoacán, Mexico

Magdalena Carmen Frieda Kahlo y Calderón was born in Coyoacán, Mexico, a town on the outskirts of Mexico City, on July 6, 1907. Her father Guillermo was of German and Hungarian descent, and her mother Mathilde was of Spanish and Indigenous heritage—Kahlo sometimes referred to herself as “mestiza,” or of mixed blood. She would often say her birth year was 1910, the year of the Mexican revolution, coinciding with the start of modern Mexico. Kahlo had three sisters, two older and one younger.

Daddy’s little girl

Kahlo was very close to her father, Wilhelm Kahlo, who arrived in Mexico from Germany. He worked various jobs, and became a photographer at the urging of Kahlo’s mother, Mathilde, who was his second wife. Of his four daughters, Wilhelm shared a close and special relationship with Kahlo, taking care of her during her many illnesses and sharing the same passion for art and photography. Wilhelm, who later changed his name to Guillermo, died in 1941, leaving the artist devastated.

LEARN ABOUT THE LIFE OF THE ARTIST BANKSY

Dig deeper into the question, “Who is Banksy?” and explore the acclaimed street artist’s work and role within street art and popular culture.

1914: Stricken with polio

Kahlo suffered many ailments throughout her life, including polio, which she contracted at age 6. While she recovered from her illness, her left leg became deformed, and the muscles in her right leg withered permanently. It left her with a limp, which she disguised by wearing long skirts. Her father recommended practicing sports to help with her recovery.

1922: Path to medicine

Kahlo showed an interest in the sciences and biology from an early age. Despite the influence of her father’s artistic nature as a photographer, Kahlo’s childhood ambition was to become a doctor. In 1922, she attended the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria, a preparatory school attached to the National Autonomous University of Mexico in Mexico City, intending to pursue a career in medicine. There, she first met artist and muralist Diego Rivera, who would eventually become her husband. He was at the university working on a mural called “The Creation,” which had been commissioned by the Mexican government.

1925: A severe bus accident awakens a passion for painting

Kahlo had by this time become involved with a group of students with whom she shared similar intellectual and political opinions. Alejandro Gomez Arias was a kind of leader within the group, and Kahlo quickly became enamored.

One day in September 1925, Kahlo and Arias, by this time an item, were traveling together when a tram broadsided their bus. Kahlo, who was just 18, nearly died in the crash. She broke her spinal column, collarbone, pelvis, and right leg and foot, and a steel handrail impaled her hip, leaving her in excruciating pain. After recovery in a Red Cross hospital, she returned home to continue her recovery, including three months in a full-body cast. During this difficult time, Kahlo began painting, finishing her first self-portrait a year later to keep herself busy.

IS ART A SMART INVESTMENT DURING INFLATION?

Access a guide to investing during inflation and learn about smart investment options such as contemporary art, real estate, and more.

32 surgeries and a lifetime of health issues

The accident forever changed Kahlo’s life: Her injuries left her in constant pain for the rest of her life. Due to the extent of her injuries, both in number and severity, she withstood some 32 operations throughout her life. She had to use metal or plaster corsets for extended periods, yet even these she turned into art.

To deal with the ever-present pain, she drank alcohol copiously and eventually became addicted to morphine. Kahlo also suffered several miscarriages, and in her 40s, she developed gangrene and had to have her right foot and, later, her leg amputated. After that, she wore a prosthesis.

Communism and political activism

Despite living through the Mexican Revolution, Kahlo did not become actively political until she entered the National Autonomous University of Mexico in 1922. While at the school, she became a member of “Los Cachuchas,” a radical campus group with deep Communist sympathies. By age 16, she was a youth member of the Mexican Communist Party. Later, in her 20s, she officially joined the organization, despite its existence being, at that time, against the law.

Political activism would be a beacon for Kahlo, both in life and art. Later in life, she served as an active campaigner for the Stockholm Appeal, a World Peace Council initiative. In 1950, this group opposed the United States’ “nuclear diplomacy” in favor of a Soviet regime’s call for nuclear disarmament in the wake of the devastating atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

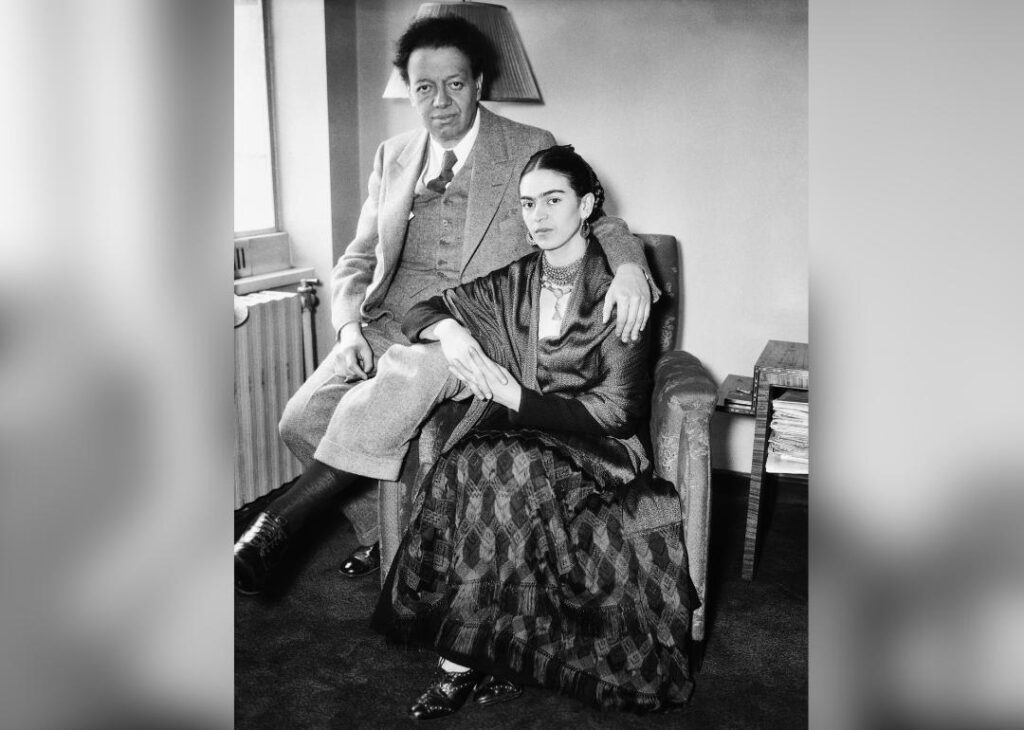

1929: Married, divorced, and remarried to Diego Rivera

While Kahlo first met Diego Rivera during her university years, they did not fully enter one another’s lives until she reconnected with him years later to ask him to assess her work. Rivera was a very well-established artist renowned for his frescos and murals. The two married in 1929 despite protests from Kahlo’s mother, who was said to have remarked that the couple resembled an elephant and a dove, alluding to Rivera’s physical appearance.

Their relationship was a tumultuous one. Rivera was known to have several affairs, including one with Kahlo’s sister. Kahlo also had several affairs of her own, with both men and women, including, reportedly, singer Josephine Baker. The couple divorced in 1939, only to remarry one year later.

Mexicanidad influence

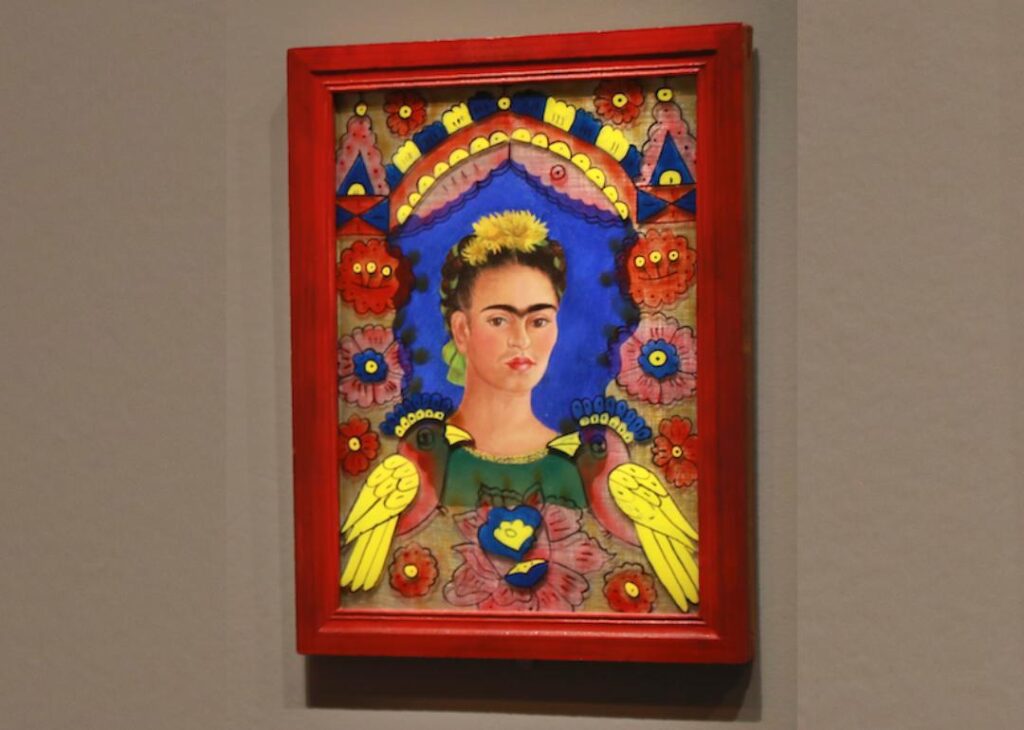

Mexicanidad influenced Kahlo’s art. People generally think of Mexicanidad as an acute pride taken in one’s Mexican heritage, manifesting in one’s manner of living—in the case of both Kahlo and Rivera, in their art and political views.

For Kahlo, Mexicanidad permeated all aspects of her daily life, from how she dressed to the jewelry she wore. She also popularized the use of skulls, traditionally used for the Day of the Dead celebrations.

1931: Trips to the US: ‘Gringolandia’

Kahlo traveled to the United States in the early 1930s after Rivera was commissioned to work on projects in San Francisco, Detroit, and New York. She disliked living in the U.S., saying it was too capitalist and “absolutely medieval.” During her time in New York, she saw the contrast between the wealthy elite that had hired her husband and the working class suffering the effects of the Great Depression.

1932: Miscarriages and abortions

When she was 6, Kahlo contracted poliomyelitis, which, while she survived without any loss of significant motor function, left her nonetheless frail. In the 1925 bus accident that left her severely injured and needing multiple surgeries throughout her life, a steel handrail impaled her, damaging Kahlo’s uterus. This injury left her unable to maintain a pregnancy successfully.

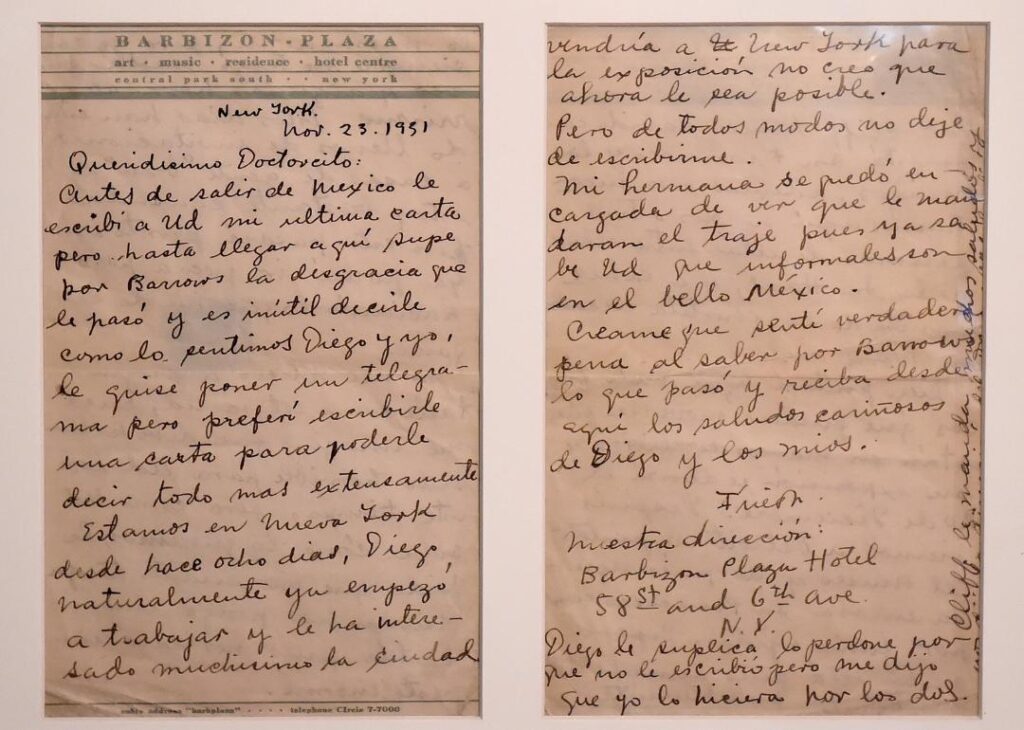

In 2007, a series of letters from Kahlo to Dr. Leo Eloesser was published, which described the artist’s struggles and emotional suffering in the wake of a miscarriage. After suffering a miscarriage while in Detroit, she depicted herself bleeding on a hospital bed in her painting “Henry Ford Hospital.” She rendered the painting on sheet metal rather than canvas at the suggestion of Rivera, who encouraged Kahlo to show her struggles in her heart and mind outwardly.

1935: Changes name in the face of rising fascism in Europe

There is some conflicting understanding as to why and to what form Kahlo changed her name in the 1930s. Some accounts hold that in 1935, amidst the rise of fascism in Germany, Kahlo adopted the Germanic spelling of her name—Frieda, a derivation of “Frieden,” meaning “peace” in German—to take a formal stand against Nazism.

Others suggest the opposite—that “Frieda” changed her name to Kahlo to move away from the German spelling and embrace her Mexican origins, just as her father had changed his name from Wilhelm to Guillermo upon his arrival in Mexico in 1891.

1937: Love affair with Leon Trotsky

Leon Trotsky was a Russian revolutionary and Marxist forced into exile by Joseph Stalin. Trotsky and his wife fled to Mexico, where Kahlo and Rivera welcomed them. Kahlo later had an affair with Trotsky while he was staying at her home in Coyoacán. Their affair was not kept particularly quiet—Kahlo dedicated a self-portrait to Trotsky in 1937.

In 1940, when Trotsky was brutally assassinated, Kahlo was held by Mexican authorities on suspicion of being the killer. Her relationship with Trotsky was well known, as were her Marxist sympathies.

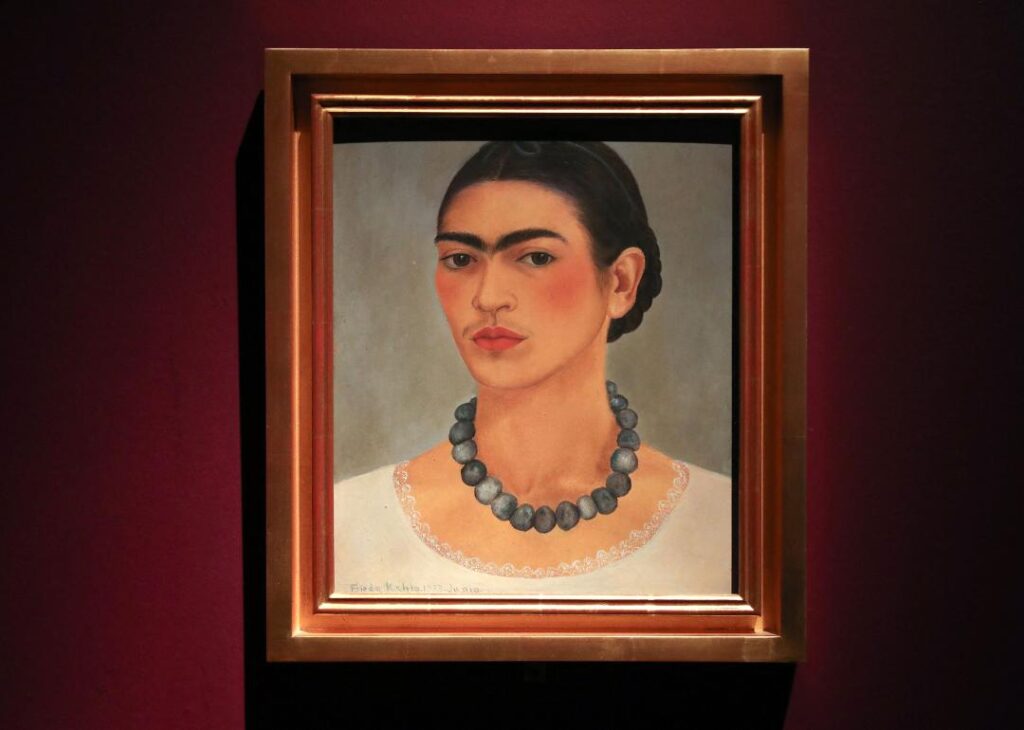

1939: First Latina artist to have a painting in the Louvre

In 1939 Kahlo became the first female Latin American artist to have her work exhibited at the famous Louvre Museum in Paris. The museum purchased a self-portrait named “The Frame,” which was an exercise in “mixed medium,” employing both aluminum and glass as base surfaces. It also introduced her as an artist in Europe, helping her climb out from underneath the stigma of being the wife of a more “successful” artist.

1938: First solo exhibition in New York City

In November 1938, Kahlo held her first solo exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York City. Her success was somewhat overshadowed by the New York art world’s referring to her as “Diego Rivera’s wife.” Nonetheless, many famous artists, including Georgia O’Keeffe, attended the exhibition, which was considered a success. Kahlo sold more than half the paintings on display, earning commissions and recognition for her unique talent.

1940s: Relationship with Chavela Vargas

Kahlo had numerous affairs with men and women while married to Diego Rivera. One such rumored affair was with singer Chavela Vargas, who immortalized the song “La Llorona.” Vargas, 12 years younger than Kahlo, even lived with her and Rivera for a time. Before her death in 2012, Vargas spoke about her romance with the famous painter. In a documentary aired in 2017, Vargas said that she was invited to a party at Kahlo’s home and that when she saw the artist, she was dazzled by her face and eyes.

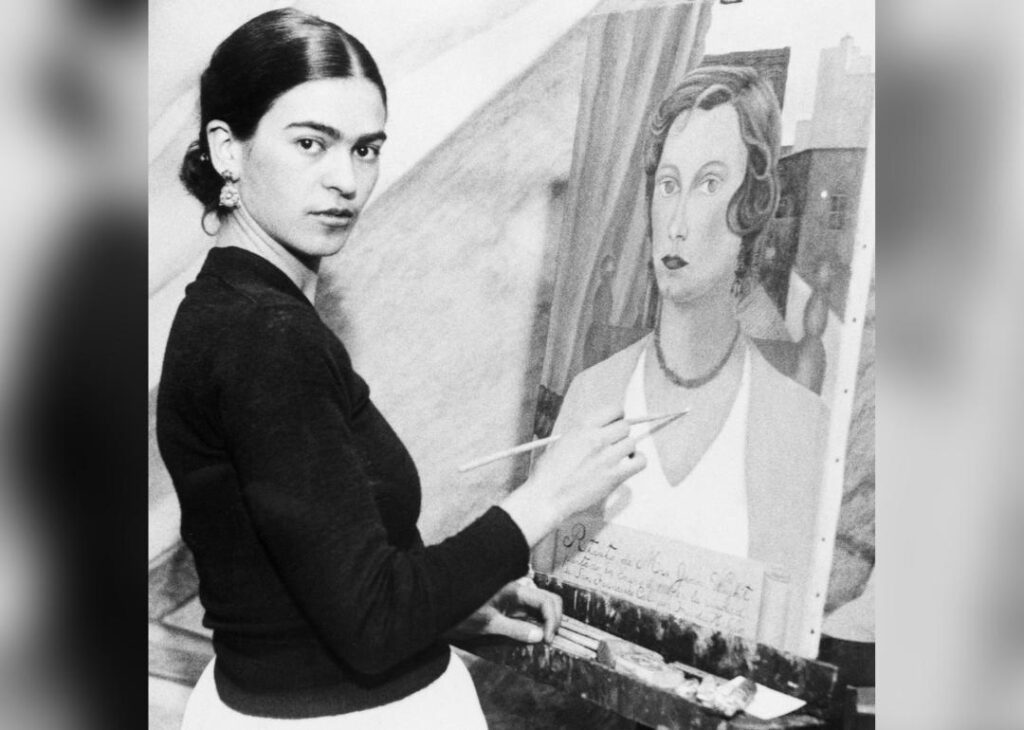

The importance of self-portraits

The number of paintings Kahlo produced in her lifetime is a bit uncertain. Some sources say it was 143, others indicate around 200, yet others say the number is 152. The lack of consensus may be due to counts including, or discluding sketches and minor drawings, as well as works presumed lost that exist only in rare photographs.

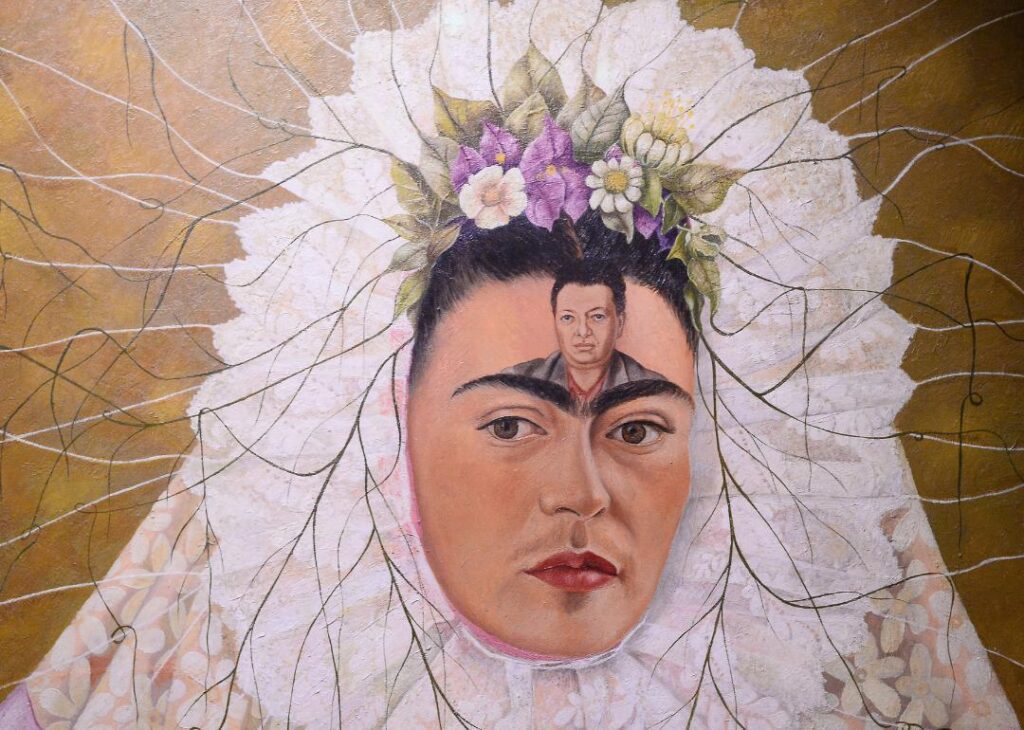

However, one relatively consistent number is the count of 55 self-portraits. While she also placed great value on using her art as a mode of political expression and discourse, she also believed that art was the most honest means of self-revelation. Kahlo was quoted saying, “I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone, because I am the person I know best.”

Her self-portraits were colorful and vibrant, portraying herself with flowers in her hair, sometimes surrounded by animals, and often in her unique fashion, which melded traditional Mexican motifs with a modern flare. Her self-portraits reflected her experiences, most notably the many operations she had to undergo, her miscarriages, and the heartbreak of her marriage and many affairs. “I never painted dreams,” she said. “I painted my own reality.”

1953: Final exhibition in Mexico City; a dream come true, but from her death bed

In 1953, the deterioration of her health led to Kahlo requiring surgery to amputate her right leg below the knee. Around this time, her drinking consumption rose, and in the wake of this most recent operation, she had formed a dependence on painkillers.

These challenges aside, Kahlo could finally fulfill her dream of holding a solo exhibition in Mexico City that spring. Due to her condition, however, she had to be taken to the exhibit by ambulance. Once there, she attended the exhibition while lying in a canopied bed decorated with pictures of friends and family, accented with papier-mache skeletons.

Unfortunately, while this exhibit—her first ever outside of a group setting—fully and formally announced her value to Mexican art, Kahlo’s health deteriorated. As her addiction to alcohol and medications intensified, her paintings grew rougher and less frequent.

July 13, 1954: Death at 47

Just over a year after her solo exhibition in Mexico City, Kahlo died of a pulmonary embolism brought on by pneumonia. There were reports that her death was a suicide, but these were swiftly debunked. Her last words recorded in her diary were, “I hope the exit is joyful, and I hope never to return.”

Her ashes are displayed at her “Blue House” (La Casa Azul) in Coyoacán, the town of her birth and death.

Since 1954: Posthumous recognitions and feminist icon

Kahlo was an artist ahead of her time in many aspects—from fashion to feminism to her artistic style. Almost 70 years after her death, Kahlo has become much more than a celebrated artist or convenient fodder for popular culture. Her paintings, which initially sold for a few hundred dollars a piece, now sell for millions. Her work has enjoyed numerous exhibitions worldwide, which continue to draw in millions of visitors. Her life story has also inspired other artists and art forms, perhaps most notably in the Academy Award-winning film “Frida,” starring Salma Hayek and directed by Broadway icon Julie Taymor.

Of a 2003 exhibition of Kahlo’s work at the Seattle Art Museum in Washington State, Houston Museum of Fine Arts curator of exhibitions Janet Landay—who was an organizer on a 1993 showing of the artist’s work—told Smithsonian magazine: “Kahlo made personal women’s experiences serious subjects for art, but because of their intense emotional content, her paintings transcend gender boundaries. Intimate and powerful, they demand that viewers—men and women—be moved by them.”